Contents

2. Operation of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism

3. Supervisory body Standards for Article 6.4 Activities

4. Transitioning Clean Development Mechanism projects

5. Next steps in the operationalisation of the PACM

6. Share of proceeds within the PACM

7. Approaches for government to take a share in proceeds and at the national level

1. Background

CMA 6 at COP 29 in November 2024 saw agreement on steps towards the final building blocks that set out how carbon markets will operate under Article 6.2 and Article 6.4 of the Paris Agreement 2015. Following this, meetings of the UN’s Article 6.4 Supervisory Body (the “Supervisory Body“) and its expert panels resulted in further developments towards operationalisation.[1]

Under Article 6.2, countries can use cooperative approaches to engage in the bilateral or multilateral trade of internationally transferred mitigation outcomes (“ITMOs“)[2] for use in reaching their nationally determined contributions (“NDCs“). Host Party governments play a fundamental role in negotiating agreements for the trade of ITMOs. Several bilateral agreements between countries already exist. For instance, in November 2024, Ghana announced that it was operationalising a digital trading platform through which it will trade ITMOs into Singapore, and in February 2025, Switzerland signed an agreement for the purchase of ITMOs generated through a Malawi-based cookstove project.[3]

Article 6.4 establishes the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism (“PACM”) which is intended to be structurally similar to other carbon-crediting programmes available through the voluntary carbon markets. The PACM builds on its Kyoto Protocol’s predecessors – Clean Development Mechanism and Joint Implementation. It will consist of standards and approved methodologies for carbon crediting projects and a registry system where Article 6.4 Activities can be registered, credits can be issued, and ownership of credits can be recorded. Credits under the PACM are known as Article 6.4 Emission Reductions (or “A6.4 ERs“).Specific advice is sought on the standards which the Supervisory Body of the Article 6.4 mechanism (“SBM”) recently published including standards relating to methodologies for Article 6.4 Activities. The scope of this note is limited to Article 6.4 and we do not consider Article 6.2 in further detail.

An overview of the operation of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism is provided in section 2 below and a summary of the Supervisory Body’s key methodological standards is outlined in section 3 below.

2. Operation of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism

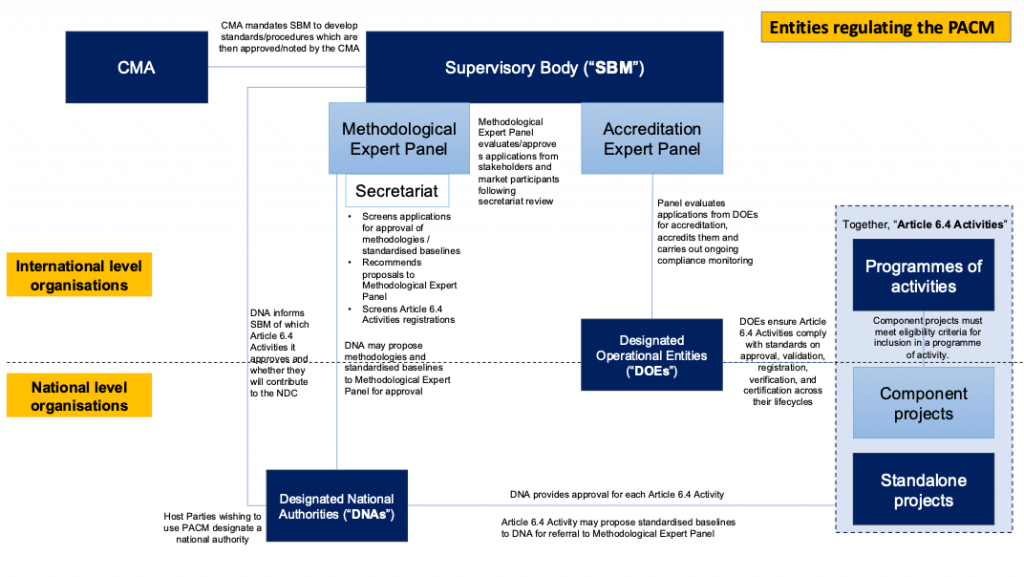

The PACM relies on several stakeholder entities which each play a role in the regulation of the carbon market, as outlined within the diagram and corresponding description of each stakeholder below.

CMA: The CMA is the governing body composed of the Parties to the Paris Agreement that oversees its implementation including the PACM. The CMA elects the Supervisory Body’s members and provides guidance on the operation of the PACM (through CMA decisions) to the SBM.[4] This includes developing and/or approving methodologies, registering activities, accrediting third-party verification bodies, and managing the Article 6.4 Registry.

The Supervisory Body (SBM): The SBM is composed of 12 members (and one alternate each) tasked by the CMA of developing and supervising the requirements and processes needed to operationalise the PACM. The Supervisory Body’s standards and procedures must be consistent with the CMA’s decisions. The standards and procedures govern all processes associated with the operation of the PACM, which include:

- the accreditation of designated operational entities (“DOEs“);[5]

- the development and/or approval of methodologies for Article 6.4 Activities and the publication (within 7 days of approval) of approved methodologies on the UNFCCC website;[6] and

- the process by which Article 6.4 Activities are approved, registered, and validated, and how emission reductions are verified.[7]

The SBM is supported by an Accreditation Expert Panel and a Methodological Expert Panel. The Accreditation Expert Panel, with the assistance of assessment teams, oversees applications from DOEs for accreditation, and the Methodological Expert Panel oversees applications from any stakeholders or market participants for approval of methodologies and standardised baselines. The Supervisory Body’s secretariat carries out initial completeness checks of applications to the Methodological Expert Panel and is also responsible for considering registration applications for Article 6.4 Activities (see section 2.1.5(F) below).

Host Parties and Designated National Authorities (“DNAs”): Each Party state to the Paris Agreement that wishes to utilise the PACM is required to designate a national authority for the purpose of overseeing the operation of Article 6.4 Activities. The key responsibilities of the DNA relate to (but are not limited to) the following:

- publicly indicating to the SBM the types of Article 6.4 Activities it would approve within the host country and how or whether such activities would contribute to the host Party’s NDC, if applicable, and the goals of the Paris Agreement;[8]

- proposing methodologies to the SBM and/or requiring certain types of Article 6.4 Activities within their jurisdiction to adhere to more stringent methodological standards or baselines (this is optional and not mandatory for the DNA); and

- considering and approving or rejecting each project within its jurisdiction before it is recommended to the Supervisory Body.[9]

Designated Operational Entities (“DOEs”): DOEs are independent organisations, which act as auditors of Article 6.4 Activities and assess their compliance with CMA decisions and relevant requirements adopted by the SBM. The SBM regulates the governance structure of DOEs and sets standards to which DOEs must adhere in order to be accredited. The SBM’s Accreditation Expert Panel accredits DOEs and monitors the performance of DOEs throughout their accreditation term to ensure that they continue to comply with standards.[10] Details of applicant DOEs and those that have been accredited are published on the UNFCCC website (available at: Accreditation | UNFCCC). Thus far, one DOE has been accredited, Carbon Check (India) Private Limited (CCIPL).

Once DOEs have been accredited by the SBM, they are able to oversee the operation of Article 6.4 Activities by following the SBM’s procedures and standards on the approval of design, validation and registration of Article 6.4 Activities. Once Article 6.4 Activities are registered, DOEs are required to verify and certify the emissions reductions and request the SBM to issue a corresponding quantity of A6.4 ERs. DOEs are required to ensure that activities adhere to their selected methodologies and periodically verify and certify Article 6.4 Activities throughout their lifecycle. Where the design of an Article 6.4 Activity changes in nature or where it reaches the end of its crediting period, there are specific procedures and standards for DOEs to ensure compliance with.[11]

Programmes of activities and projects: Projects for the generation of A6.4 ERs may be operated as standalone projects, or several component projects may form a programme of activities (collectively referred to as “Article 6.4 Activities”). In the case of programmes of activities, each component project must meet the eligibility criteria of the programme of activity which would have been validated by a DOE as part of the programme design document.[12] A programme of activity may operate at a multi-jurisdictional level (i.e. with operations across different countries), however each component project, must fall within the geographical boundary of one host Party.

Approval and registration process

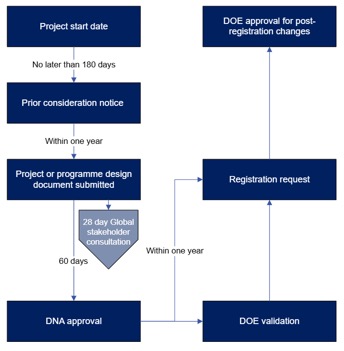

Article 6.4 Activities undergo steps for registration under the PACM as set out in the flowchart below and in corresponding steps (A) to (G):[13]

(A) Prior consideration notice: The participants of Article 6.4 Activities must firstly give prior consideration to the benefits of the mechanism in relation to the project and submit a notification to the UNFCCC of their intention to seek registration. This notification must take place no later than 180 days after the project start date.

(B) Project/programme design document: Within one year of this notification, the participants of the Article 6.4 Activity must submit a project or programme of activity design document in line with the SBM’s standards and approved methodologies to the UNFCCC. This design document is then published on the UNFCCC website.

(C) Global stakeholder confirmation: The design document then goes through a 28-day period of global stakeholder consultation which involves consultation, analysis and comments, from any Parties, stakeholders or observer organisations, in relation to the document’s compatibility with the SBM’s rules.

(D) DNA approval: The host Party DNA must also consider the design document, particularly its likely implications on the host country’s NDC, and within 60 days of publication, it submits its approval or rejection of the Article 6.4 Activity which is published on the UNFCCC website. If the proposal relates to a programme of activity with component projects over many jurisdictions, each relevant host Party DNA must provide this approval.

(E) DOE validation: The design document is then submitted to a DOE and is validated following an assessment of whether it complies with the Supervisory Body’s activity standards.

(F) Registration: Following validation, the participant of the activity can submit a registration request with the secretariat and obtain registration. The submission to the secretariat is required to take place within one year of the DNA’s approval.

(G) Post-registration changes: At any point following registration, if there are any changes to the design of the Article 6.4 Activity or if it comes to the end of its crediting period, it must again be approved and validated in accordance with the above.

Verification and ongoing monitoring

Once Article 6.4 Activities have been approved and registered, they face ongoing monitoring by DOEs throughout their lifecycles through monitoring reports. DOEs use monitoring reports to assess and audit the measurement of emission reductions and certify whether A6.4 ERs should be issued in respect of them.[14] DOEs then submit a request for issuance of the A6.4 ERs through a dedicated platform on the UNFCCC website.[15]

3. Supervisory body Standards for Article 6.4 Activities

The standards for Article 6.4 Activities under the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism are set in accordance with paragraph 35 of the Annex to Decision 3/CMA.3 “Rules, Modalities and Procedures for the Article 6.4 Mechanism” (the “RMP“) which provided the overarching power to the Supervisory Body to set methodological standards. The standards regulate the implementation of methodologies for Article 6.4 Activities and require them to:

- implement baselines for emission reductions which are adjusted downwards and account for issues associated with suppressed demand (as set out at section 3.4 to 3.6 below),

- meet requirements in relation to additionality (as set out at sections 3.8 to 3.11 below),

- have a robust process in place to address the risk of leakage, and

- where the Article 6.4 Activity is a greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emission removal activity (eg reforestation or carbon capture projects), meet standards related to mitigating the reversal risk of removals.

There are further requirements that form part of the Supervisory Body standards, such as the need for activities to contribute to sustainable development, however our analysis is limited to the above factors.[16]

In relation to each requirement, there are overarching principles approved by the CMA and set out in the RMP.[17] The overarching principles state that mechanism methodologies shall:

- encourage ambition over time;

- encourage broad participation;

- be real, transparent, conservative, credible and below “business as usual”;

- avoid leakage, where applicable;

- recognise suppressed demand;

- align with the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement;

- contribute to the equitable sharing of mitigation benefits between the participating Parties; and

- in respect of each participating Party, contribute to reducing emission levels in the host Party, and align with its NDC, if applicable, its long-term low GHG emission development strategy, if it has submitted one, and the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement.

(together, the “CMA principles“)

Standardised baselines

Establishing baseline emission levels

Baseline levels of emissions against which A6.4 ERs are measured for each Article 6.4 Activity are required to be calculated in accordance with the “business-as-usual” (“BAU”) principle.

The BAU principle requires the participant to identify a scenario in which the reduction activity had not taken place and use projected emissions as a reference point for which to calculate emissions reductions against.[18] In calculation of the BAU baseline, participants are required to apply a performance-based approach which:

- uses the best available technologies (that are economically feasible and environmentally sound in the situation);

- ensures that the baseline is set at least at the average emission levels of the best performing comparable activities providing similar outputs in similar social, economic, environmental, and technological circumstances; and

- is based on actual or historical emissions, adjusted downwards to ensure alignment with the CMA principles.[19]

Adjusting baselines downwards[20]

The standards provide that baselines should be adjusted downwards through a mechanism which compares baselines set in accordance with the BAU principle against those set in accordance with the CMA principles. At present, the process has not yet been fully developed. The Supervisory Body, in its meeting of 11 to 14 February, acknowledged that further clarity will be needed and streamlined standards in this regard are in the process of being developed.

The standards, in their current form, provide as follows:

- The difference is calculated between emissions levels as the result of a performance-based approach (as set out above) and the BAU scenario emission levels.

- The project design document should use factors and quantitative methods for the downward adjustment of emissions which considers economic viability of critical mitigation activities, large-scale transformation and decarbonisation technologies, negative emission approaches while ensuring that methodologies are aligned with the long-term temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

- Where the difference at (1) shows a greater downward adjustment than the approach at (2), no further adjustment is needed. Where (1) is a lesser adjustment than at (2), further adjustment is required.[21]

Recognising suppressed demand

The standards do recognise that some of the least developed countries are likely to face situations where there is a lack of access to energy, basic goods and services, and economic development to achieve this access would inevitably result in an increase in GHG emissions. In these situations, a BAU baseline cannot be used to measure the Article 6.4 reductions against as it will not account for the growth in emissions for the purposes of development for meeting basic needs. Instead, the concept of suppressed demand is recognised, and the Supervisory Body may include benchmarks and default factors in specific methodologies to account for these situations.[22]

Standardised baselines

Standardised baselines may be implemented by a host Party or the Supervisory Body to cover Article 6.4 Activities of a certain type or within a certain jurisdiction. This may for instance occur where the leakage impact of certain project types is being measured or where the host Party has a specific national policy requiring additional standards to be met. But this is not a mandatory requirement and where no standardised baselines are prescribed, individual Article 6.4 Activities can apply their own baselines using the above approved approaches.

If standardised baselines are applied, they must be approved through either:

- a top-down process, where they are proposed by the Supervisory Body’s Methodological Expert Panel; or

- a bottom-up process, where Article 6.4 Activities may propose standardised baselines to their relevant DNA which, if approved, are submitted to the secretariat, who may recommend to the Methodological Expert Panel that the standardised baseline be adopted. The panel independently assesses the proposal and if they approve, the standardised baseline along with any Supervisory Body guidance is published and made publicly available on the UNFCCC website.

In either case, in developing standardised baselines the standards require that they are in accordance with the business-as-usual, downwards adjustment and suppressed demand principles as outlined above. The host Party and Supervisory Body are also required to consider how and the extent to which Article 6.4 Activities should be aggregated under a standardised baseline. In doing so, they should consider that:

- the default level of aggregation would be aggregating together facilities or equipment producing similar types of outputs within a geographical boundary or a subregion;

- a default group of facilities should be disaggregated when significant dissimilarities exist in the performance of facilities or groups of facilities in the region; and

- disaggregation should not result in certain projects falling under several standardised baselines.[23]

Additionality

All Article 6.4 Activities are required to demonstrate that the project would not have occurred in the absence of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism. In making this assessment of additionality, the national policies, legislative requirements, and existing climate frameworks of the host Party are considered. [24] The initial assessment of additionality needs to be conducted by Article 6.4 Activities prior to their registration and must be considered as part of the prior consideration of the benefits of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism.[25] Following the publication of the project design documents, it is the role of the DOE to ensure additionality requirements are met at each stage of the activity cycle.[26]

The Supervisory Body requires that methodologies contain provisions demonstrating additionality through:

- a regulatory analysis: demonstrating that the proposed activity represents a mitigation that exceeds any mitigation required by law or regulation within the host country; and

- the avoidance of lock-in: the activity should not lock in any emissions, technologies or carbon intensive practices that fail to comply with the CMA Principles.

- Financial additionality must also be demonstrated within methodologies by using either:

- the default approach of an investment analysis which considers whether an activity is financially viable in the absence of revenue from A6.4 ERs, or where an investment analysis is not sufficient;

- a barrier analysis which is an assessment of the barriers to the implementation of the activity, such as financial and institutional barriers within national policy and current practices within the activity sector or geographic area; and

- a common practice analysis which should complement the investment and barrier analysis and demonstrate that the measure or technology is not already widespread by considering the extent to which the technology or project type is prevalent in that sector and region.

- The Methodological Expert Panel met between 11 and 14 February 2025 and approved a further standard which elaborates and provides examples on several of the concepts outlined above such as regulatory analysis, investment analysis, lock-in, barrier analysis and a common practice analysis. For a more detailed overview of these concepts, refer to “Demonstration of additionality in mechanism methodologies”.[27]

Leakage

Article 6.4 Activities should be designed in a way to minimise the risk of leakage, adjust downwards for any remaining leakage and provide data within methodologies relating to leakage.

As part of the project approval process, Article 6.4 Activities are required to define the boundaries of the activity, including the physical boundary i.e. using GPS coordinates; the particular sources of GHGs to be included; any sinks that are included; and which GHGs are included.[28] These parameters are necessary for an assessment of leakage.

The Supervisory Body requires that methodologies include provisions to identify potential sources of leakage, implement measures to minimise these sources, provide a description of how mitigations are conducted, and include robust, transparent, and user-friendly measurement provisions for specific sources of potential leakage.[29]The following sources of leakage are identified in the standards along with some examples of mitigations against them:

- Where the Article 6.4 Activity involves changes to processes and the replacement of inefficient equipment (i.e. baseline equipment) with more efficient equipment for the purpose of achieving an emission reduction, the baseline equipment may still be used outside the activity boundary. In this case, the standard suggests a mitigation which involves the scrapping, decommissioning or destruction of baseline equipment so that it cannot be used by others outside the activity boundary.[30]

- The standard states that where resources have competing uses from Article 6.4 Activities and activities outside the activity boundary, this could lead to a net change in emissions outside the boundary or shifts of pre-project activities that lead to a net change in emissions outside the boundary.[31] At present, no further guidance is provided on this concept, however the Supervisory Body may choose to clarify this at a later date.

- Baseline emission levels for Article 6.4 Activities would have been set in accordance with BAU processes, which may diverge from existing processes over time.[32]

- Article 6.4 Activities may require resources and materials from upstream and downstream sources which are produced through processes which have a negative impact on emissions, in which case, activities are required to conduct a life-cycle analysis on such products or materials.[33]

- Other potential means of minimising sources of leakage identified by the Supervisory Body include:[34]

- deducting emission reductions from credited volumes taking into account the relevant equipment’s lifetime;

- applying higher-level elements such as a standardised baseline applied at a higher level of aggregation and be regularly updated;

- aligning relevant aspects of activity design and implementing activities with an existing higher level crediting programme;

- and/orupscaling implementation of activities at a higher (national/sectoral) level.

The Article 6.4 Activity should also consider that the DNA of the host Party may also have other requirements in place in relation to leakage.

The standard states that activities which fall within Article 5.2 of the Paris Agreement,[35] which relates to the mechanism for REDD+ projects (ie projects aimed at protecting and using forests sustainably), must also adhere to the above standards on leakage.[36]

Removal project requirements[37]

The Supervisory Body requires that Article 6.4 Activities based on removal of GHGs from the atmosphere comply with additional requirements aimed at mitigating the reversal risk of the removal of GHG emissions. In addition to removal activities, the standard also includes within scope “emission reduction activities with reversal risks”,[38] however this is not a term that is defined, and it remains to be seen the extent to which non removal activities with a reversal risk would be caught by the additional requirements. Article 6.4 Activities caught within the scope of this standard are referred to as “Removal Activities”.

How are removals calculated?

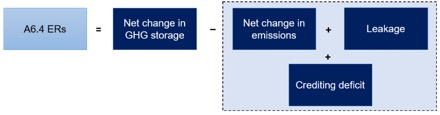

The standard requires that Removal Activities use the following mechanism to account for removals for the purpose of determining the corresponding number of A6.4 ERs to be issued.[39]

Where the net change in GHG storage calculated is negative, this amounts to a reversal of a removal and requires A6.4 ERs issued in respect of the Removal Activity to be remediated (see section 3.21 below).

Where the net change in GHG storage calculated is positive, A6.4s can be issued in respect of this and are calculated as:

In the calculation of A6.4 ERs:

- a net change in emissions refers to the total emissions in the activity scenario deducted by the total emissions in the baseline scenario; and

- a crediting deficit refers to a scenario where a negative number is calculated in respect of A6.4 ERs in a crediting period.

Requirements for removal activities

The removal standards require that Removal Activities:

- include provisions for the robust monitoring of removals within their methodologies and include a monitoring plan within their project or programme design documents (which are approved as per section 2.1.5(B) above);[40]

- report on data collected related to the calculation of net removals through a monitoring report in accordance with monitoring plans approved within their methodologies, the frequency of such reporting is required to be between 1 and 5 years depending on the type and risk of removals associated with it and is required to continue after the end of the last crediting period of the Removal Activity;[41]

- conduct a risk assessment for reversals of removals, including a risk mitigation plan and an overall percentage-based risk rating of reversals for the Removal Activity;[42] and

- report to the Supervisory Body any observed events (both avoidable and unavoidable) involving the release of GHGs that were stored as part of the Removal Activity, the process for which is set out in the standard.[43]

Remediation of reversals

To account for the risk of reversals within Removal Activities, the standards require for the creation of a Reversal Risk Buffer Pool Account within the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism registry. Each time a Removal Activity requests for the issuance of A6.4 ERs, a percentage of A6.4 ERs, based on the percentage-based reversal risk rating of the activity, (see section 3.20.3 above) is placed within this buffer pool account.[44]

A6.4 ERs within the buffer pool account are accessible only by the registry administrator and cannot be accessed by the Removal Activities. Where a reversal of GHG storage materialises, the Supervisory Body may require the administrator of the Reversal Risk Buffer Pool Account to cancel a corresponding amount of A6.4 ERs held in this account in respect of the relevant Removal Activity.

The Supervisory Body has noted that it may consider implementing further guidance for Removal Activities in respect of reversals which materialise due to unavoidable events.[45]

4. Transitioning Clean Development Mechanism projects

One of the features of the Paris Agreement Crediting Mechanism is that it acts as a successor mechanism to the Clean Development Mechanism (“CDM”) which was established under the Kyoto Protocol and operates similarly to its successor. However, projects under the CDM have faced criticism for their lack of robust methodologies.

The Supervisory Body allows for projects operating under the existing CDM to be transferred to the PACM provided that:

- applications for their transition are made in accordance with prescribed procedures and time limits;

- projects use methodologies in compliance with the methodological standards set out at section 3 above; and

- projects comply with additional design requirements.

Procedure and time limit

The initial deadline for CDM activities to submit transition requests to the secretariat was 31 December 2023 which has now passed. Projects which submitted this request would have undergone a global stakeholder consultation process (as outlined at section 2.1.5(C) above) following submission. It is now the role of DNAs to consider transition requests which may be approved and notified to the Supervisory Body by 31 December 2025, following which, the Supervisory Body will consider and approve or reject.[46]

A further requirement in respect of transitioning CDM activities, is that they must submit a request for renewal of their crediting period within a year of the approval of the transition to the PACM by the Supervisory Body.[47]

To date only one project transition request has been approved by its host Party and the Supervisory Body, the Republic of Korea’s Clean Energy Program in Myanmar.[48]

Methodologies[49]

CDM activities transitioning to the PACM, may, until the earlier of the end of their existing crediting periods and 31 December 2025, continue to apply their current methodologies as long as they comply with the Article 6.4 standards on methodologies. Where existing methodologies do not comply with standards, transitioning activities must submit a revised methodology.

The transitioning activity may however choose to apply a new methodology prior to its expiry which may be necessary for its effective operation. For instance, in the case of programmes of activities, new component projects are not permitted to be approved into the programme unless a revised methodology has been applied.

Until the most recent standards were agreed by the Supervisory Body, it was understood that transitioning activities would not include afforestation or reforestation projects under the CDM. However, the CMA 6 (November 2024) accepted that reforestation and afforestation projects can transition as long as they meet the additional methodological requirements related to removal activities as set out in section 3 above.[50]

Additional requirements

The following additional requirements are placed upon transitioning CDM activities:

- CDM activities that currently use specifically listed methodologies, that have been identified as having a risk of non-permanence of emission reductions, are required to take further steps if the projects will continue to use that methodology following transition to the PACM.[51]

- For activities using certain methodologies which have been identified as having a risk of negative emission reductions, participants must examine each monitoring report for that activity and determine whether there has been an accrual of net negative emission reductions. If there has been, these net negative emission accruals are to be taken into account in emission reductions occurring from January 2021 to the end of the current crediting period.[52]

- For activities using methodologies which have been identified as having a non-permanence risk for emission reductions, project participants are encouraged to ensure that the fraction of non-renewable biomass value (which is a metric used to calculate emission reductions from projects that reduce demand for fuelwood or charcoal) and the discount factor for addressing leakage are based on the latest data and information.[53]

Furthermore, transitioning activities must be of the type indicated by the host Party’s DNA to the Supervisory Body as those they would consider approving under the PACM; provide a real, measurable and long-term climate change related benefits; ensure they comply with the sustainable development tool and report on emission reductions achieved, or expected to be achieved, based on standardised global warming potentials published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[54]

5. Next steps in the operationalisation of THE PACM

Methodologies

The Methodological Expert Panel is currently in the process of drafting further standards related to baseline setting which intends to elaborate and provide further analysis on the methodological standards on baseline setting (as outlined above).

The next meeting of the Methodology Expert Panel is scheduled to take place on 7 to 11 April 2025 at which it will consider methodologies submitted to it prior to 24 February 2025 (if any) and may consider or approve draft standards on methodologies.

So far, no methodologies have been published on the UNFCCC website however, they are expected to be proposed and approved by mid-2025.

Mechanism registry

The key next step for the operationalisation of the PACM is for the Supervisory Body to implement the registry for A6.4 ERs.

During its meeting between 11 and 14 February 2025, the Supervisory Body adopted an overarching procedure for the operation of the registry which sets out:

- the registry functions, including account types and how to set up accounts;

- the procedure for transactions, including issuance of A6.4 ERs, transfers, retirement and cancellation; and

- how the registry will interact with other systems.[55]

The Supervisory Body has called for further stakeholder input on the registry for discussion at future meetings.

6. Share of proceeds within the PACM

The Adaptation Fund was established to contribute to the development of climate adaptation projects within developing countries. It was initially partly funded by the PACM’s predecessor mechanisms under the Kyoto Protocol. However, the Adaptation Fund will now also be funded through the share of proceeds for adaptation from the PACM through three ways.[56]

One contribution to the Adaptation Fund consists of a levy that Parties to the Paris Agreement are required to contribute 5% of A6.4ERs issued by the PACM. Another contribution agreed on bythe SBM and the CMA is the deduction of 3% of the issuance fee paid for each request for issuance of A6.4ERs and collectively transfer them as monetary contribution to the Adaptation Fund. The third funding stream is through a periodic monetary contribution that the SBM reviews annually considering the remaining funds resulting from the income from fees and expenditure for operating the PACM and decides on timing and amount of funds to be transferred to the Adaptation Fund.[57] Together, these three financial contributions are referred to as the “share of proceeds for adaptation”. [58]

Least Developed Countries (“LDCs“)[59] and Small Island Developing States (“SIDS“) are granted an exemption from the share of proceeds for adaptation, which they may choose to make use of. This means that LDCs and SIDS are not required to contribute a share of the proceeds from their carbon market activities to the Adaptation Fund.[60]

The exemption acknowledges the unique vulnerabilities and limited financial capacities of LDCs and SIDS, allowing them to participate in carbon markets without the additional financial burden.

For completeness, we note that there is also a share of proceeds to cover administrative expenses. The CMA has set out the level of fees for this.[61] All these fees are waived for activities in the LDCs and SIDS.

7. Approaches for government to take a share in proceeds and benefits at the national level: Fiscal carbon market models in africa

African carbon markets are evolving with various models and initiatives aimed at reducing carbon emissions and promoting sustainable development across the continent. Given the extent of technical skills, regulatory frameworks and resources required to establish carbon markets, African countries are pursuing different models depending on the circumstances. For instance, certain countries have opted for a national carbon market framework, whilst others have relied more heavily on voluntary carbon markets.

National Carbon Market Frameworks

Some African countries are developing their own national carbon market frameworks to facilitate the trading of carbon credits within their borders. These frameworks aim to create a stable regulatory environment, attract investment, and support the development of carbon reduction projects. Salient examples include Rwanda and Ghana,[62] while other such as Nigeria are in the process of developing such frameworks.

Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM)

These markets allow companies and individuals to voluntarily offset their carbon emissions by purchasing carbon credits from projects that reduce or remove greenhouse gases. VCMs are attractive to African countries that do not wish to establish a formal carbon market or do not currently have the technical capacity or resources to regulate carbon market related activities. VCM participants are engaged in various projects focused on reforestation, renewable energy, and sustainable agriculture. African countries with active VCM projects include Gabon, Zambia, Kenya,[63] and Tanzania.

Given that the voluntary carbon markets are not regulated under specific laws, the main fiscal benefits for countries result from the income tax that is due under the revenue generated in the country.[64] To ensure that relevant revenues would be captured, countries may want to prescribe specific local content requirements for carbon projects, including that the trading entity must be incorporated locally/domestically, local ownership requirements and local spend requirements.

Case study: Ghana

Ghana’s new Environmental Protection Act (2025), Act 1124, (EPA), aims to address critical environmental challenges, streamline existing environmental laws, and modernise Ghana’s environmental governance framework. Chapter 5 of the EPA focuses on strengthening Ghana’s climate change governance to ensure a coordinated, effective, and internationally aligned response to the climate crisis. Section 159 mandates the EPA to develop regulations for the carbon market framework. For now, Ghana’s framework on international carbon markets and non-market approaches (an executive policy, often referred to as the “framework document”) continues to provide for the country’s arrangements on carbon markets.

The framework document was developed by the Government of Ghana, through the Ministry of Environment, Science, Technology, and Innovation, to raise carbon finance to support its NDC and drive foreign direct green investments to benefit local businesses. It also forms part of Ghana’s greenhouse gas mitigation policy package. It emphasises transparency, environmental integrity, and sustainable development.

The framework document is divided into two volumes, each focusing on one of the two provisions on market approaches under Article 6 of the Paris Agreement:

Volume 1 provides the operational framework for the Article 6.2 cooperative instrument. It includes policy, regulatory, and operational information on Ghana’s engagement in the cooperative instrument and the voluntary carbon market.

Volume 2 offers guidelines for domesticating the Rules, Modalities, and Procedures (RMP) of the Article 6.4 mechanism. The Carbon Market Office performs the functions of a designated national authority. Its functions include engagements with the Supervisory Body, developing baseline approaches and other methodological requirements and approving the transition of CDM project activities or programmes.

A third volume is planned, which will contain additional guidance on implementing Article 6.8 non-market approaches.

Case study: Kenya

Kenya has emerged as a leader in Africa’s carbon market, leveraging its renewable energy projects, reforestation initiatives, and sustainable agriculture to generate carbon credits. The country has issued over 52.4 million carbon credits through mechanisms like the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM) and Voluntary Carbon Markets (VCM). Key projects include geothermal and wind energy, improved cookstoves, and water purification systems.

Kenya’s Climate Change Act, amended in 2023, and Climate Change (Carbon Markets) Regulations, 2024 provide a framework for carbon trading, allowing participation in voluntary markets, in the Article 6.2 cooperative instrument, and in the Article 6.4 PACM. Among other things, the Act provides for environmental impact assessment requirements for carbon market projects; provision of social and environmental benefits; public land-use projects; dispute resolution; fees; offences and penalties.

Under the Act both Government and private promoters can engage in carbon trading through either bilateral or multilateral trading agreement vehicles. The Act also offers a complete approach to emissions mitigation through carbon reduction credits, removal or sequestration credits, technologies, and projects on the whitelist, and emphasises the significance of carbon removal and sequestration strategies (including afforestation, reforestation, nature-based solutions, and advanced removal technologies).[65]

In respect of benefit sharing specifically, both the Act and the Regulations contain provisions on social and environmental benefits (see section 23E in the Act and sections 22 and 29 in the Regulations, provided in the Annex below for ease). These sections require every land-based carbon project to be implemented through a community development agreement (“CDA”). A template for the CDA is set out in the Fourth Schedule of the Regulations. The CDA must outline the relationships and obligations of the proponents of the project in public and community land where the project is under development. Projects on public or community land must contribute annually to local communities at a minimum of 40% of annual earnings for land-based projects and 25% for non-land-based projects, after accounting for operational costs.[66]

It is also worth noting that the Kenyan Parliament is considering The Natural Resources (Benefits Sharing) Bill.[67] This Bill was proposed in 2022 to address the lack of accountability and transparency in natural resources benefit sharing. The Bill is currently in the Third Reading in Parliament. It proposes a framework for the sharing of benefits of natural resource exploitation between resource exploiters, the national government, county governments, and local communities. The Bill considers different models, including collection of royalties and fees (Part III) as well as benefit sharing agreements (Part IV).

Despite Kenya’s progress, challenges remain, such as regulatory fragmentation, high transaction costs, limited technical capacity and disputes with impacted local and indigenous communities.

Annex

Kenya, Climate Change Act, Cap. 387A, Legislation as at 15 September 2023

23E. Provision of social and environmental benefits

- A project undertaken pursuant to this Act shall specify the anticipated environmental, economic or social benefits of the project.

- For purposes of subsection (1), the benefits shall include—

- a) removal of greenhouse gases from the atmosphere and avoidance of emission of greenhouse gases in order to meet Kenya’s international obligations;

- b) incentives that promote offset projects;

- c) increase of carbon abatement in a manner that is consistent with protection of Kenya’s natural environment;

- d) improved resilience to the effects of climate change; or

- e) achievement of Kenya’s greenhouse gases emissions targets.

- Every land-based project undertaken pursuant to this Act shall be implemented through a community development agreement which shall outline the relationships and obligations of the proponents of the project in public and community land where the project is under development.

- The National Government and the respective county government where the project is situated shall oversee and monitor the negotiation of the community development agreement with project proponents and the stakeholders.

- A community development agreement shall include provisions on the following—

- a) the stakeholders of the project including the project proponents, the impacted communities, the National Government and the county government where the project is being undertaken;

- b) the annual social contribution of the aggregate earnings of the previous year to the community, to be managed and disbursed for the benefit of the community;

- Provided that—

- i) in land-based projects, the contribution shall be at least forty per centum of the aggregate earnings; and

- ii) in non-land-based projects, the contribution shall be at least twenty-five per centum of the aggregate earnings;

- c) the manner of engagement with local stakeholders, especially the impacted communities;

- d) the sharing of the benefits from the carbon markets and carbon credits between the project proponents and the impacted [communities];

- e) the proposed socio-economic development around community priorities; and

- f) the manner of the review or amendment of the agreement, which shall be at least every five years.

- A community development agreement entered into pursuant to this section shall be recorded in the National Carbon Registry.

- Every carbon project undertaken pursuant to this Act shall take into consideration and aim to improve the environmental, economic, social and cultural wellbeing of the community around the project.

- The national government and the respective county government where the project is situated shall enforce the community rights negotiated under a community development agreement negotiated under section 23E.

- The Cabinet Secretary may prescribe additional requirements relating to the formulation of the community development agreement.

Climate Change (Carbon Markets) Regulations, 2024

22. Project design document

…

4) The project design document submitted under this regulation shall be accompanied by the following—

…

c) a community development agreement for land-based carbon projects on public and community land in the manner set out in the Fourth Schedule;

…

29. Annual social contribution

1) The annual social contribution to the community in carbon projects on public and community land shall be as provided in section 23E(5) of the Act:

Provided that the annual social contribution for—

a) land-based projects shall be at least forty per centum of the aggregate earnings of the previous year less cost of doing business; and

b) non-land-based projects shall be at least twenty-five per centum of the aggregate earnings of the previous year less cost of doing business.

2. The annual social contribution shall be included in the Community Development Agreement set out in the Fourth Schedule.

3. A private carbon project on private land shall not be required to disburse the annual social contributions under section 23E(5)(b) of the Act.

4. The management and disbursement of the benefits for the community shall be undertaken by a community project development committee in the manner set out in the Community Development Agreement.

[1] For an overview of the Supervisory Body and its expert panels, refer to section 2.1.2 below.

[2] ITMOs are a form of carbon credits representing a reduction or removal of greenhouse gas emissions from the atmosphere and are traded between countries under Article 6.2.

[3] See Ghana Moves Forward with Digital Carbon Market ITMO Trading into Singapore – ZERO13, and Purchase agreement on ATEC‘s Article 6.2 eCook 100% data-auditable carbon project in Malawi. For an overview of cooperative approaches, visit the UNFCCC website at: Cooperative approaches | UNFCCC.

[4] For an overview of how the CMA and Supervisory Body interact, see “Information note: Decision and documentation framework.”

[5] See generally “Standard: Article 6.4 accreditation” and paragraph 5 of Decision 3/CMA.3.

[6] See generally and paragraph 50 of “Procedure: Development, revision and clarification of methodologies and methodological tools” and paragraph 5 of Decision 3/CMA.3.

[7] See paragraph 6 of Decision 3/CMA.3 and generally “Standard: Activity standard for projects“, “Standard: Activity standards for programmes of activities“, “Standard: Article 6.4 validation and verification standard for projects“, “Article 6.4 validation and verification standard for programmes of activities“, “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects” and “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for programmes of activities“.

[8] See paragraph 26, Annex, Decision 3/CMA.3 Rules, modalities and procedures for the mechanism established by Article 6, paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement (“RMP“).

[9] See paragraph 40, RMP and section 4.4 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects“.

[10] See paragraph 24, RMP, and “Standard: Article 6.4 accreditation“, “Procedure: Article 6.4 accreditation” and “Performance monitoring of the Article 6.4 designated operational entities“.

[11] See paragraph 24, RMP and generally “Standard: Article 6.4 activity standard for projects” and “Standard: Article 6.4 activity standard for programmes of activities“.

[12] See paragraph 46 RMP and paragraph 8 of “Standard: Article 6.4 activity standard for programmes of activities“.

[13] See sections 4 and 5 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects” and of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for programmes of activities“.

[14] See paragraph 51, RMP and for a detailed overview of how the verification and certification process is conducted, see section 8 of “Standard: validation and verification standard for projects.”

[15] See paragraphs 52 to 55, RMP sections 7 and 8 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects.”

[16] As part of the RMP, host countries have to provide (“shall” requirement), as part of the approval of the activity, confirmation that and information on how the activity fosters sustainable development in the host country. To assist host countries with this, the CMA tasked the Supervisory Body to develop a sustainable development tool. This tool has been published and ensures Article 6.4 Activities uphold the principle of “do no harm”, foster sustainable development, and contribute to the 17 Sustainable Development Goals. See the Article 6.4 sustainable development tool at: https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/A6.4-TOOL-AC-001.pdf

[18] See paragraphs 28 to 29 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies.”

[20] The principle of adjusting emissions downwards based on the CMA principles is required by the RMP (paragraph 36), and is provided for under section 4.7 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies.” However, the Methodological Expert Panel has recognised that the downward adjustment mechanism requires further development and a further draft standard is under consideration.

[21] See paragraphs 44 to 47 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies.”.

[22] See paragraphs 56 to 59 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies.”

[23] See paragraph 67 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“.

[24] See paragraph 38 to 39, RMP.

[25] See Section 4.2 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects” and Section 5 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“.

[26] See Standards: “Activity Standards for Projects“; “Validation and verification standards for projects“; “Activity Standards for Programmes of Activities“; and “Validation and verification standard for programmes of activities“.

[27] See “Standard: Demonstration of additionality in mechanism methodologies.” https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/A6.4-STAN-METH-003.pdf

[28] See paragraph 45 of “Standard: Activity Standards for Programmes of Activities“

[29] See paragraphs 81 to 86 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[30] See paragraph 84(a) and 85(b) of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[31] See paragraph 84(b) of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[32] See paragraph 84(c) of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[33] See paragraphs 83(e) and 84(d) of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[34] See paragraph 85 of “Standard: Application of the requirements of Chapter V.B (Methodologies) for the development and assessment of Article 6.4 mechanism methodologies“

[35] Article 5.2 of the Paris Agreement encourages countries to take action to slow, stop and reverse deforestation through a variety of means including using policy approaches to promote sustainable management of forests and enhance forest carbon stocks.

[36] There is another mechanism in place for REDD+ projects which was established under Decision 1/CP.16. This provides for positive incentives for activities relating to reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, and the role of conservation, sustainable management of forests and enhancement of forest carbon stocks in developing countries; and alternative policy approaches, such as joint mitigation and adaptation approaches for the integral and sustainable management of forests, while reaffirming the importance of incentivising non-carbon benefits associated with such approaches.

[37] See paragraph 6(c) of Decision 3/CMA.3 and “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[38] See paragraph 10 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[39] See section 4.4. of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.“

[40] See section 4.1 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[41] See section 4.2 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[42] See section 4.6.1 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[43] See section 4.6.2 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[44] See section 4.6.3.1 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[45] See paragraph 53 of “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism.”

[46] See paragraph 73, RMP and generally “Procedure: Transition of CDM activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[47] See paragraph 200 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for projects” and paragraph 244 of “Procedure: Article 6.4 activity cycle procedure for programmes of activities.”

[48] Transitioning projects and their status in the approval process are published on the UNFCCC website, available at: https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/paris-agreement-crediting-mechanism/transition-of-cdm-activities-to-article-64-mechanism#CDM-projects-approved-by-Host-Parties-for-transition-to-Article-64-mechanism

[49] See Section 6.2 of “Standard: Transition of CDM activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[50] See paragraph 21 of “Decision -/CMA.6 Further guidance on the mechanism established by Article 6,

paragraph 4, of the Paris Agreement” and “Standard: Transition of CDM activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism” (as amended) and “Standard: Requirements for activities involving removals under the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[51] See paragraphs 29 and 30 of “Standard: Transition of CDM Activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[52] The relevant methodologies for which this requirement applies are listed at paragraph 32 (a) to (k) of “Standard: Transition of CDM Activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[53] The relevant methodologies for which this requirement applies are listed at paragraph 33 (a) to (d) of “Standard: Transition of CDM Activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism“.

[54] See section 6 of “Standard: Transition of CDM activities to the Article 6.4 mechanism” (as amended).

[55] See “Procedure: Article 6.4 mechanism registry.”

[56] For an overview of the Adaptation Fund, see: https://unfccc.int/Adaptation-Fund.

[57] Decision 7/CMA.4 para 15.

[58] See paragraph 67 RMP in Decision 3/CMA.3, annex, chapter VII.

[59] Also see The least developed countries report: Leveraging carbon markets for development available online at https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/ldc2024_en.pdf.

[60] See paras 19-20 of Decision 5/CMA.6, https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/CMA_6_agenda%20item15b_AUV_2.pdf

[61] See paragraph 68 RMP and paras. 50-55, Annex I, Decision 7/CMA.4.

[62] See Ghana’s framework on international carbon markets and non-market approaches https://cmo.epa.gov.gh/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/Ghana-Carbon-Market-Framework-For-Public-Release_15122022.pdf

[63] See https://www.fao.org/faolex/results/details/en/c/LEX-FAOC220092/

[64] For example, the Third Schedule of the Kenyan Income Tax Act Cap 470 provides that a company operating a carbon market exchange or emission trading system, that is certified by the Nairobi International Financial Centre Authority, shall pay corporate taxes at rate of 15% for the first 10 years from the year of commencement of the operations.

[65] Kenya, Africa Net Zero Toolkit available online at https://www.netzerolawyers.com/africa-investment-toolkit/kenya

[66] See section 23E of the EPA and also section 29 of The Climate Change (Carbon Markets) Regulations, 2024, No. 84 of 2024

[67] A copy of the Bill is available at http://www.parliament.go.ke/sites/default/files/2023-08/Senate%20Bill%20no6%20on%20the%20Natural%20resources%20benefit%20sharing%20bill%202022.pdf